Victory Reclining

by Marianna Maruyama ︎︎︎Some time ago Staria began de-cluttering, starting with unloved books, outgrown clothes and broken furniture. Next to go were cracked dishes, useless documents, expired medicine, dead batteries, doubles of anything, dried out paint – all the things that no longer served. Having nothing to do with joy (sparked or not), nor a matter of “going minimalist”, Staria began to shed.

The next round saw Staria giving books away to friends, returning rings and mementos back to former lovers, offering photo albums to family members, and donating artworks to collectors. Personal archives consisting of lecture notes, drawings, performance documentation, sculptures and paintings, started to fracture, dissemble, and disperse, radiating outwards.

It looked like Staria was simply moving out as things went into boxes, bags, and then out the door to friends, charity, or the garbage. Whatever money was left was given to strangers. It happened slowly, without acknowledgement.

After a few months, Staria’s space started to look downright monastic. All that remained was a mattress and sheets (no pillow), a bottle of olive oil, salt, tobacco and a pipe, matches, a single print, a small cooking pot, and some rice.

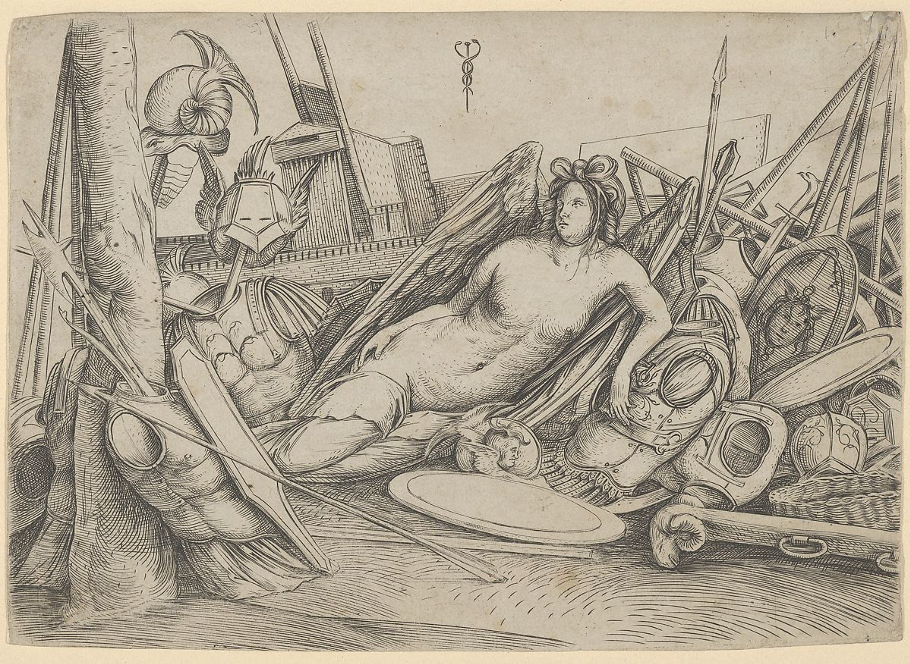

I know all this because I first met Staria around this time. I’d been invited to visit the impressively empty apartment to discuss my research on the 16th century artist Jacopo de’ Barbari (Jacob the Barbarian, or Jacob the Foreigner). As I’d recently had my heart broken (an understatement since it wasn’t only my heart, but a full-body and soul break) I was, as is said in American parlance, a hot mess. Meeting this elusive figure was a much-needed distraction from my inner life, which was an emotional minefield. I didn’t know how Staria looked, but I was aware of the reputation: an extraordinarily humble person in possession of an unrivaled intellect.

Staria, I soon found out, was disarmingly handsome: masculine-feminine extraordinaire, with dark eyes, a touch of grey hair, and the intelligent, weathered hands of a craftsperson.

I remember entering the foyer, empty but for the long shafts of light stretched across high ceilings: Holding out bare hands as a cup, Staria gives me a mouthful of water and it drips down my chin and neck. We move quietly to the kitchen where I’m offered a handful of rice from the pot, and a fingertip of salt. I take my time, my lips finally kissing the palm when I reach the last mouthful. Staria takes a few drops of olive oil, spreads it across my lips and returns with another mouthful of water. I have never experienced true hospitality until now, I think: I’ve not even merely grasped its essence.

Staria takes me to the bedroom, where de’ Barbari’s print stands out in stark contrast to the emptiness. I respond to the sudden awareness of my own subjugation to objects, ideas, the past, and, most immediately – and urgently – the weight of my clothes. Taken by hand to the bed, resting head over chest, covered by softly worn sheets; I feel at once and for all time the meditation of hands on the skin of my beautiful back.

Another mouth-to-mouth sip, the taste of steamed rice, salt, and oil on the tongue and lips, the imprint of palms now memorized by legs, back, belly, knees, neck. Reddish cheeks, and a tiny amount of finely shredded tobacco in a slender Japanese pipe. Light it and inhale. Be honest with yourself, there actually are winners and losers in love. In this moment, for once, know how it feels to be victorious over possession.